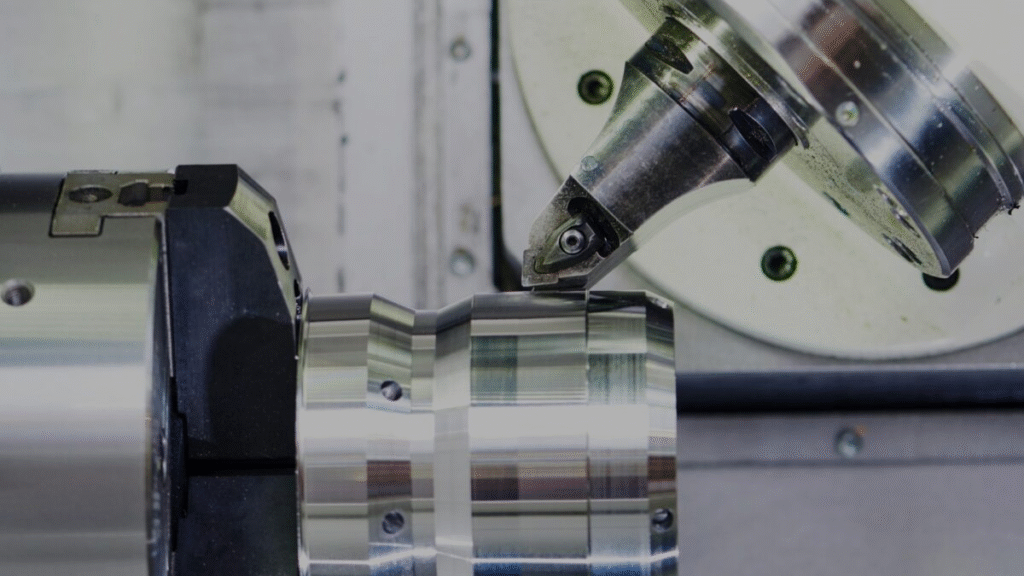

Chatter is one of those shop-floor problems that feels both obvious and mysterious. Obvious because you can hear it, see it on the surface, and measure its impact on tool life. Mysterious because it persists even after you “do everything right”: new cutters, different feeds and speeds, altered stepovers, even a fresh toolpath. When chatter won’t go away, it’s tempting to blame the machine or the CAM strategy. But in many real production cases, the root cause sits in a quieter place — the workholding loop. If the workpiece, clamps, fixture, or fixture interface allow vibration to grow, no tool upgrade will fully solve it.

This article is a practical guide to diagnosing chatter from the fixture up. We’ll walk through what chatter really is, why it often survives tool changes, and how to isolate whether the problem is coming from the base interface, the fixture structure, or the clamping method itself.

What chatter actually is (in plain terms)

Chatter is a self-excited vibration in the cutting system. It emerges when the energy added by the cutting process exceeds the damping capacity of the tool–part–fixture–machine loop. Once the system finds a resonant frequency, the vibration reinforces itself. That’s why chatter marks look periodic and why the noise sounds like a repeating howl rather than a random squeal.

The important implication is this: chatter is not just a tool problem. It’s a loop problem. The loop includes the spindle, toolholder, tool, workpiece, clamps, fixture, fixture interface, and machine structure. Weakness in any piece can allow vibration to grow.

Why new tooling sometimes doesn’t help

If your vibration loop is unstable, a sharper cutter may reduce chatter temporarily — but it won’t remove the underlying resonance. Similarly, changing speeds can shift the chatter band away from a resonant frequency, but only within a narrow window. That’s why you may “find a sweet spot” for one tool but lose it when the tool wears slightly or when you switch to another operation. The system is still fragile, so the chatter comes back.

The core diagnostic question becomes: where is the compliance (flex) living?

Start with the simplest test: shorten the loop

Before you tear into fixtures, run a quick “shorten the loop” test:

- Reduce tool stick-out by 20–30% if possible.

- Increase tool diameter or use a stiffer holder.

- Reduce axial engagement while keeping chip load similar.

- Re-run the cut.

If chatter drops dramatically, the dominant compliance is likely in the tool–holder side. If chatter barely changes, the compliance is likely on the workholding side — the part or its support.

Part-side compliance: is the workpiece behaving like a spring?

Thin walls, long overhangs, and small contact areas make parts act like tuning forks. If you’re machining a tall pocket wall or a slender bracket, the part itself can resonate even if everything else is rigid. Typical clues:

- Chatter shows up only after a certain wall height is reached.

- It’s worse near free edges or corners.

- Changing toolpath direction changes the chatter tone.

Solutions here are geometry-aware: add temporary supports, change the cut order to keep stiffness longer, or alter stock to allow a stiffer rough state. But if the part is stiff enough on paper and still chatters, look one layer down: clamping and fixture support.

Interface-side compliance: the hidden lever you can’t see

Many chatter cases come from micro-movement at the fixture-to-machine interface. A fixture that is “tight” is not necessarily rigid. If the interface allows minute slip or rocking, the whole structure becomes a lever arm, amplifying vibration at the cutting edge.

Two common causes:

- Bolt-down interfaces that don’t fully locate in shear, so they creep under cyclic load.

- Contaminated mating surfaces (chips, burrs, oil film) that prevent full contact.

A standardized, fully seated docking baseline reduces this internal compliance because it defines position mechanically and increases contact stability. Some shops achieve this by moving to modular zero-point interfaces like 3r systems, which help fixtures return to the same rigid seat and reduce micro-rocking that can feed chatter.

Fixture-body compliance: when the fixture is the spring

Even if your interface is solid, the fixture itself can flex. The usual offenders are thin plates, tall risers without ribs, and overhangs that place mass far from the mounting plane. A quick way to detect fixture compliance is simple:

- Put a dial indicator on the part or fixture at the cutting zone.

- Apply hand pressure in the direction of cutting force.

- If you can see measurable deflection, the cut will see more.

Fixture stiffness upgrades are often straightforward: add ribs, shorten unsupported spans, increase plate thickness, or move clamps closer to the cut zone. Remember that five-axis clearance fixtures are especially prone to leverage; if you had to make the setup tall, you must make it proportionally stiffer.

Clamping-side compliance: uneven forces create motion

Even with a stiff fixture, clamping can be the weak link. If clamping forces are unbalanced, the part can “walk” under cyclic cutting loads. This motion is often too small to detect visually, but it’s enough to excite vibration.

Symptoms include:

- Chatter that worsens mid-cut as forces build.

- Chatter that improves when clamping torque is increased — until distortion appears.

- Repeat chatter at the same machining direction.

Balanced, symmetric clamping can reduce this effect by keeping the part centered and loading it evenly against supports. In many general-purpose setups, a self-centering module such as CNC Self Centering Vise is used to apply opposing forces uniformly so the workpiece doesn’t bias toward one jaw and start micro-slipping.

A structured troubleshooting flow

Here’s a practical order of operations you can use on the shop floor:

- Verify tool-side stiffness (run the shorten stick-out test).

- Check part stiffness (does chatter correlate with wall height or free edge?).

- Inspect clamping for balance (torque consistency, jaw contact, support locations).

- Measure fixture deflection under hand load.

- Clean and re-seat the interface; re-torque in a consistent pattern.

- If needed, redesign for stiffness or add temporary supports.

The key is to change only one variable at a time. Chatter is a system resonance, so multiple changes can mask the root cause.

Don’t forget damping

Rigidity is half the story; damping is the other half. Two systems with identical stiffness can behave differently if one dissipates vibration better. Practical damping helps include:

- Larger contact areas at locators and jaws.

- Ensuring full surface contact at base interfaces.

- Avoiding “hard-point” clamping that creates a pivot.

- Using anti-vibration toolholders when tool-side compliance is real.

Closing thought

Chatter feels like a cutting problem because it appears at the cutter. But the cutter is only the messenger. When chatter persists across tools and parameters, the workholding loop is the first place to look. A stable system starts from the base interface, passes through a stiff fixture body, and ends with balanced clamping. Fix the loop, and chatter usually disappears — not for one run, but for good.